Given the myriad and ferocious debates over copyright and ownership in the news today, it is difficult to believe that anyone would ever not want to take credit for their work, and yet literary forgery has a long and strange history. It may well be as old a practice as writing itself, and incorrectly attributed works – intentionally or not – can be found in nearly every period of literature.

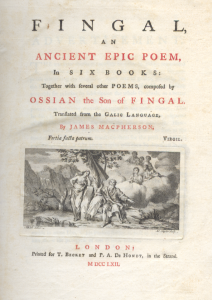

When I first came to the Walter Havighurst Special Collections library seven months ago, I was taking some time to explore the stacks and get to know the collection. It was then that I came upon our editions of the Ossian poems, which represent a moment in literary history I have always found fascinating. In the middle of the 18th century, a Scottish poet named James MacPherson published his translation of the works of Ossian, said to be a bard from third century Scotland. The Ossianic poems are narrated by Ossian in his old age, recounting triumphs and tragedies surrounding his family, especially his father Fingal; the characters themselves are loosely connected to the Irish heroes Oisin and his father Fionn mac Cumhaill. This cycle of epic poetry rapidly became an international sensation and is credited as a major influence of both the Gaelic revival and the Romantic movement.

However, while the tales of Ossian had captured the minds and hearts of Enlightenment philosophers and Romantic artists, scholars of language and history (most famously Samuel Johnson) were not far behind in pointing out historical and linguistic inconsistencies of MacPherson’s supposed translation. Under increasing pressure, MacPherson was unable to produce the original Gaelic manuscripts for his translation and the Ossianic cycle has become known as one of literature’s most famous forgeries. In many ways, it is an even odder twist that its spurious origins are what the Ossianic cycle is now best remembered for. On its own it is a stunning work of literature, both in story and in style, and at its publication Ossian was widely hailed as a challenger to Homer’s crown as king of epic poets. Yet by some compulsion, MacPherson felt obligated to reject authorship of his own work in favor of a legendary figure of the past.

Frontispiece from a 1543 Italian edition of Dares and Dictys as well as other (generally spurious) works

He was not the first, either. In the late Classsical and early Medieval periods, a pair of works surfaced claiming to be eye-witness accounts to the Trojan War. Dares Phrygius and Dictys Cretensis, both figures briefly mentioned in Homer’s epics, were respectively attributed with authorship of the De Excidio Troiae Historia (‘History of the Destruction of Troy’) and the Ephemeridos Belli Troiani (‘Chronicle of the Trojan War’), which enraptured European audiences with stories of the Trojan War more accessible than Homer’s Ancient Greek. To much of Medieval Europe, Rome was held as an ideal model of a state and individual nations sought national histories that connected them to or mirrored Roman history. Like Virgil’s Aeneid, many nations constructed legends beginning with the fall of Troy, and combined volumes of Dares Phrygius and Dictys Cretensis spread through the many languages of Europe as a basis for these new legends. Some six centuries before MacPherson, Geoffrey of Monmouth composed his Historia Regum Brittaniae (‘History of the Kings of Britain), which began with Brutus, a descendant of Aeneas and conqueror and first king of England. Like MacPherson, Geoffrey claimed to have been given a manuscript – ‘quendam britannici sermonis librum vetustissimum’ (a certain very old book in the British language) – from which he based his history. However, literary criticism was somewhat less rigorous in the twelfth century and the truth about this certain book remains unknown. The Trojan beginnings of his history, though, can likely be linked to the popularity of the pseudepigraphies of Dares and Dictys.

There is a fair amount of controversy surrounding Shakespeare’s signature, but I don’t think any of it involves whether or not he spelled his name ‘Willam’

Not all forgeries, however, have had spurred cultural movements or national identities. Another famous falsification was the so-called ‘Ireland Shakespeare forgeries’. Shortly after MacPherson, an Englishman named Samuel Ireland publicly announced that his son William had found a collection of four hitherto lost and unknown plays by William Shakespeare. As with the Ossianic cycle, controversy soon arose regarding these ‘newly found’ works of Shakespeare and, like MacPherson, Ireland was accused of forgery. Both MacPherson and Ireland pushed back against their accusers, producing new documents to defend their forgeries, although these new pieces did little to change skeptics’ minds. Eventually, William Ireland publicly confessed to have fabricated the documents he gave his father but even this was considered by many to be part of a grander scheme by William and his father Samuel. These controversies were extremely damaging to the Irelands and, lacking MacPherson’s talent, the Ireland Shakespeare forgeries are today only remembered for their scandal.

For reasons we can only guess at, throughout history there have been authors who have felt compelled to ascribe ownership of their own labor to others. Most curious are those such as MacPherson, whose works on their own were nothing short of masterpieces regardless of the author, yet they lived their lives in breathless denial of their own works. Here in the Walter Havighurst Special Collections we are fortunate to not only have many of these significant – if spurious – works, but also the subsequent criticisms and defenses. What do you think drove these writers? Stop by the library to read some of these bizarre moments of literary history and decide for yourself!

TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK LANGUAGE BY

Marcus Ladd

Special Collections Librarian