Charlotte, Queen Consort of Great Britain, later the United Kingdom and Hanover (1744-1818) by Allan Ramsay

Many librarians, archivists, and academics who work with rare books and manuscripts may publicly critcize the portrayal of their professions in films like The Da Vinci Code and National Treasure, but secretly many dream about solving ancient mysteries or uncovering shocking secrets. Though very few in the profession are lucky enough to discover something so earth-shattering that it can challenge centuries of belief or accepted fact, many of us who work with special collections materials solve little mysteries and uncover fascinating stories from the past on a regular basis. Every rare book on the shelf in a special collections or archives has the potential to lead its reader down a path of discovery, whether it’s through the study of its text, its production, or its provenance. Provenance in the book world is simply the record of a book’s previous ownership. Discovering who owned a book and documenting how it may have traveled over space and time to end up on the shelf of a rare book and special collections library can be one of the most rewarding, entertaining, and even sometimes thrilling aspects of the work we do. Just ask my colleague Masha Stepanova who wrote about an exciting find in our de Saint-Rat Collection last week in her blog post. The following is a brief story of how a shelf reading project in our department led to the re-discovery of another item in our collections with an impressive provenance…

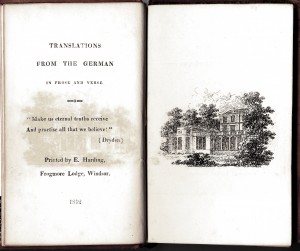

As part of an ongoing shelf reading project, our student workers, supervised by my colleague Jim Bricker, are barcoding our book collections. In order to apply a unique barcode to an item, the catalog record must be edited. Meghan Pratschler, one of our undergraduate student workers, discovered that one of the books on her project truck had a call number but not a catalog record, so the book ended up on my desk. Nothing about this volume seemed noteworthy at first and the title Translations from the German in Prose and Verse, though descriptive, was not very catchy. It looked to be a typical early nineteenth century volume of religious poetry, but when I went to find a catalog record for the title in OCLC/WorldCat, I noticed right away that only 30 copies were printed. So it was definitely a limited edition and only 13 other libraries in North America and England reported owning a copy today. The next thing I noticed was the unusual imprint, “Printed by E. Harding, Frogmore Lodge, Windsor 1812”, so I thought perhaps this was an early private press title of some kind based in someone’s residence.

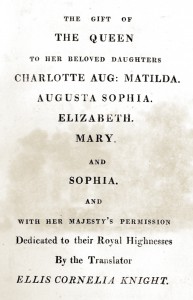

The printed dedication page reads: “The gift of the Queen to her beloved daughters Charlotte Aug: Matilda. Augusta Sophia. Elizabeth. Mary. and Sophia. and with Her Majesty’s permission dedicated to their Royal Highnesses by the translator Ellis Cornelia Knight.” Realizing the connection between the English royal family and Windsor, the location in the imprint, I became even more curious about this slim volume.

Upon further searching, I found out more about the book and its origins. The translator of the text, Ellis Cornelia Knight (1757-1837), was an accomplished writer who was a companion to both Queen Charlotte (1744-1818), wife of King George III, and later her daughter, Princess Charlotte Augusta.

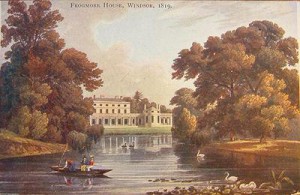

The book was produced at a private press overseen closely by Knight and Harding, a job printer in Windsor, especially for the Queen’s daughters. The quality of the printing is not particularly fine, but the volume does include a pleasant engraving of Frogmore Lodge. Frogmore Lodge, better known as Frogmore House, was a seventeenth century country estate near Windsor Castle. Queen Charlotte and her daughters used the estate as a country retreat, similar to Charlotte’s contemporary Marie Antoinette’s Estate at Versailles. Just the fact that a truly “rare” book commissioned by Queen Charlotte, with a text translated by her companion from the original German, and printed at her country home ended up on the shelf at a university library in Oxford, Ohio made this a fun find. I shared what I had discovered about the volume with Meghan, the student worker who originally “found” the book on the shelf, and the rest of the staff in Special Collections. And here’s where the provenance comes in…

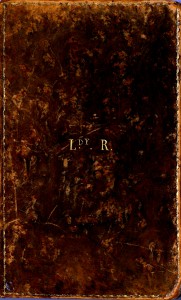

The only truly distinguishing characteristic of Miami’s copy was the original mottled calf binding with “Ldy. R.” stamped in gilt on the front cover. Who was the mysterious Lady R? Everyone in the department was curious. Since none of Charlotte’s daughters, for whom the book was printed as a gift, had names which began with the letter “R” (and they would be styled “Princess” or “H.R.H.” most likely anyway), I immediately thought that Lady R. was probably a member of the royal household, such as a Lady of the Bedchamber, commonly referred to as a lady-in-waiting. A quick search didn’t provide any immediate leads and I set the book aside in my office to return to when I had a free moment. However, Meghan, our student worker, beat me to it! She located an official listing of the Queen’s Household which included an entry for Cornelia Jacoba Waldegrave, Lady Radstock, who was one of the Women of the Bedchamber from 1799-1818. There were no other clear candidates for Lady R. in Queen Charlotte’s inner circle and the date, 1812, also lined up. While we cannot definitively know whether Cornelia is in fact our Lady R., it seems highly likely.

So who was Lady Radstock? Cornelia Jacoba van Lennep (1763-1839) was born in Turkey to a wealthy Dutch merchant family. She married William Waldegrave, first Baron Radstock (1753-1825), a distinguished Admiral in the Royal Navy and a Governor of New Foundland, in 1785. Though the historical record seems to contain very little about Lady Radstock, beyond her family’s genealogy, there is a portrait of her family in the collections of the Rijksmuseum, the Dutch national museum, in Amsterdam. The painting by Antoine de Favray from about 1771 depicts Cornelia, at approximately eight years old, in a blue dress seated on the floor. It’s pretty amazing to think that that little girl born faraway and long ago in the Ottoman Empire, who married a Canadian governor and naval hero and became a lady-in-waiting to the Queen of England, once held this book in her hands, a “gift of the Queen.” Unfortunately, there are no other marks of ownership on this presentation copy and it is virtually impossible to trace the book’s provenance after it was in the possession of Lady Radstock. Perhaps we can, instead, indulge ourselves and imagine that this book’s journey to the shelves of Miami’s Special Collections was just as fascinating as its origins.

In the meantime, we’ve already had an undergraduate student stop by our reading room to see this recently discovered treasure (she’d heard about it from John Bickers, another of our stellar student workers in Special Collections) and that same student is now exploring other books in our collection as the basis for a possible capstone project!

Kimberly Tully

Special Collections Librarian