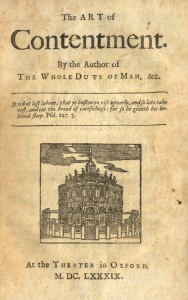

I’m a sucker for a book with a fancy provenance and I’ve written about some of my favorites in our collections here and here. And since it’s always nice to end the work week on a high note, I thought I’d indulge myself once again by writing a blog post on another book I found while cataloging pre-1800 titles in our backlog. The book is a rather commonplace devotional work on the subject of contentment, entitled The Art of Contentment. The book was published “At the Theater in Oxford” in 1689 and is attributed to the English clergyman Richard Allestree (1619-1681). Allestree was a prominent Royalist and supporter of the High Church tradition in the Anglican faith. According to modern scholarship, he also penned the extremely popular English Protestant devotional work, The Whole Duty of Man, first published anonymously in 1658 at the end of Oliver Cromwell’s rule.

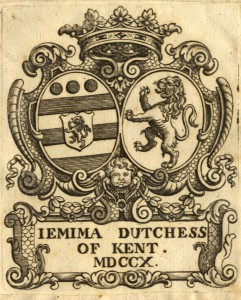

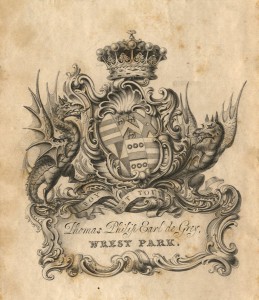

As part of the cataloging of an early printed work, or any item in special collections for that matter, it is important to include copy-specific provenance information (if it exists) in the catalog record, such as manuscript signatures, inscriptions, library stamps, or bookplates. This book had two striking armorial bookplates, one belonging to “Jemima Dutchess of Kent” dated 1710, and another early nineteenth century bookplate belonging to “Thomas Philip Earl de Grey, Wrest Park.” After recording this information in the record, I did a little investigating just for fun to see who these members of the English nobility were…

Jemima Crew (1675-1728) married Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Kent, and they had six children, before she died and he remarried in 1729. Her portrait shown here was done by prolific portrait artist Charles D’Agar. Since the Duke had no surviving children at the time of his death, his titles eventually became extinct, but it is clear that this book (and another in our collection by the same author with the same bookplates) remained at his country estate near Silsoe in Bedfordshire in the east of England. Wrest House, shown here in an engraving from 1708, would have been where Henry and Jemima raised their young children in aristocratic splendor.

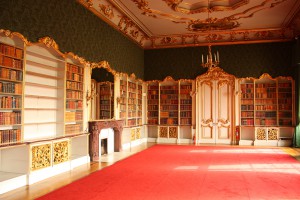

Thomas de Grey, 2nd Earl de Grey (1781-1859), whose bookplate adorns our book as well, eventually inherited the estate and rebuilt the house between 1834 and 1840. An aside for fans of the popular BBC show Downton Abbey who might be interested to know that there really were historical Lord Granthams: due to a title inherited from his father, de Grey was known as Lord Grantham for most of his life. de Grey was a Tory statesman who served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland from 1841-1844. The Wrest Park estate contains gardens that were originally designed by George London and Henry Wise for Jemima’s husband, Henry Grey, in the early eighteenth century, and later modified by the famous landscape architect Capability Brown (1716-1783). Shown below is the restored library at Wrest Park, now open to the public, where this book may have once sat on the shelf.

Many ask how books like this, once owned by duchesses and earls living on luxurious estates centuries ago, end up in academic libraries here in the United States. Many estates went bankrupt in the early twentieth century as the power and influence of the British aristocracy began its rapid decline and the contents, including libraries, of homes like Wrest Park were sold to pay debts. These books would often end up in the stock of auction houses, antiquarian booksellers , or private collectors. Many of Miami’s early printed works were collected by either Marcus Selden Goldman, a Miami alum and literature professor at the University of Illinois, or Howard Robinson, a Miami literature professor, both of whom later donated their collections to the Libraries. However, there is a Miami University connection to Wrest Park that, if pursued further, might shed more light on another chapter in this particular book’s story. Whitelaw Reid, who graduated from Miami in 1856, was the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom between 1905 and 1912. During his tenure as ambassador, he often “rented” Wrest Park during the summers. Is it possible that Reid himself purchased some of the Wrest Park library?

Linking the physical book to its historical “journey” from printer to owner(s) to library shelf has always been one of my favorite aspects of working with rare books and I like to take every opportunity I can to highlight the rich early print materials in the Walter Havighurst Special Collections.

Kimberly Tully

Special Collections Librarian