In recognition of Preservation Week (April 30-May 6), new Preservation and Conservation Librarian Eric Harrelson explains what preservation, archives and special collections mean to him.

Charles Merewether said in his introduction to the 2006 collection of writings about the role and significance of archives in contemporary art titled The Archive, that archives are “the foundation from which history is written.” This quote stuck with me. It may be a little self important, but the sentiment is true, at least in my opinion. Without archives and special collections, history begins to fade, the edges become soft, and the facts start to disappear, replaced by vague notions, outdated opinions, or deliberate falsehoods. In the simplest terms, the archive is where primary sources are held. These primary sources may be documents full of serious, quantitative information, such as letters, decrees, or policy statements from rulers and important figures in a given society. But, it can also contain artifacts of a more mundane nature. Everyday objects that were part of a regular person’s daily routine that shed light on what their lives were actually like.

It is not unusual for many of us to think of history as a series of dry facts: wars, dates, length of empires, etc. Significant cultural events that encompassed decades, even centuries reduced to a few ticks on a timeline, quickly mentioned in a semester-long sprint to the exam finish line then filed away in our brains, unused, and eventually forgotten. In the archive, however, history is preserved in all of its rich and multifaceted glory. Timelines and wars are all well and good, but history is more than just queens, generals, trade routes and military campaigns.

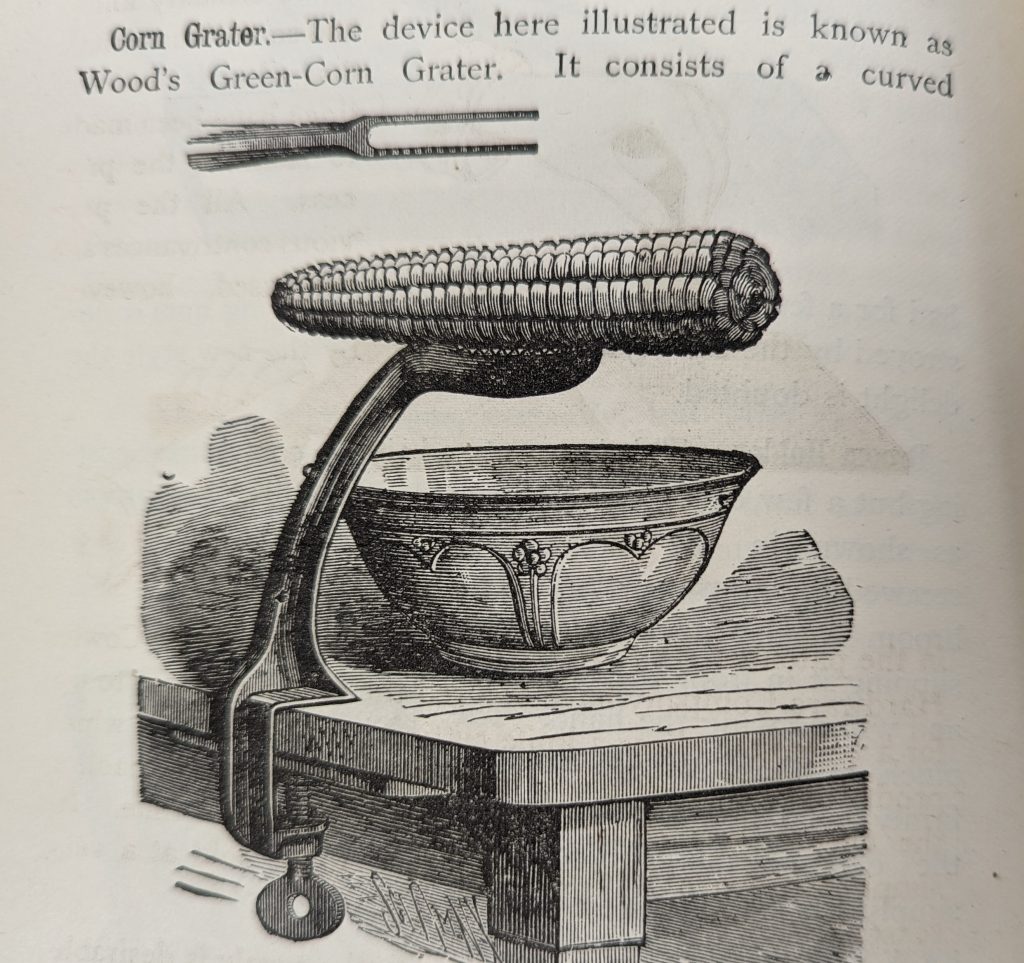

History is about life and living, how our predecessors worked, fought, learned, wrote, made art, loved, and died across the centuries. While we can never meet those people or experience what they experienced first hand, we can interact with what they left behind. Recipes for their food, explanations of how they made their clothing, tools they used, what their housing looked like, how they spent their summers, their winters, their holidays. These everyday remnants let us see just how clever, resourceful, creative, and intelligent our ancestors really were. It can be tempting to fall into the mindset that we are somehow more evolved than our ancestors, to think that we are fundamentally different from them. Smarter, more capable, more enlightened. But, that simply isn’t the case. Biologically, we are virtually identical to the people that hunted in nomadic familial communities, first domesticated animals, and built the Roman Aqueducts. It is easy to forget that fact when we look at all the incredible advances we have made and seemingly impossible technologies we have created over the years. I believe that it is important to maintain a connection to those who have come before us, and archives and special collections help us accomplish this.

I was drawn to this profession because of that connection to history, and because of the love I have for old and broken things. I enjoy taking an everyday object that has been used and abused over the years, one that most folks would likely send to the landfill and giving it some love and attention. Whether that object be a piece of furniture, an old machine, or an article of clothing, bringing that object back from the dead gives me not only satisfaction, but allows me to feel a connection to whomever owned it before I did. I believe that preserving and experiencing everyday objects from the past connects us in a more profound way to our history and our ancestors than simply looking at a picture, or reading about figures and dates in a classroom history book.

In order to maintain this connection, we need to maintain access to primary sources, whatever form they may take. As a Preservation Librarian, it is my duty to ensure that these objects and the information they contain remains usable and accessible. How that looks is different for every object. Some are high circulation books or other written materials, and those need to be repaired when they incur damage, reinforced when they show wear, or upgraded to prevent damage that is likely to occur from heavy circulation. Some objects may be unique, very old, fragile, and irreplaceable. These items need to be treated with a delicate touch, and are not intended for heavy use. The goal is to ensure no further damage occurs, and the integrity of the item is preserved for as long as possible. There are some objects that are, unfortunately, damaged beyond reasonable repair, but that also contain useful information that is peculiar and warrants preservation. In these cases, the object is often digitized, and the resulting images can preserve the information contained within the object as well as give a visual record of the object. This way while a researcher may not be able to access the object itself, they can have the next best thing.

Ultimately, archives are here to provide access to primary sources, information that is not readily available elsewhere. The role of the Preservation Librarian is to ensure that the information remains accessible. In archives and special collections, we are the stewards of the past, and as Merewether says, we provide “the foundation from which history is written.”

For more information on Preservation Week presented by Core and the ALA, visit https://preservationweek.org/ And for more information about what the Walter Havighurst Archive and Special Collections has to offer, visit https://spec.lib.miamioh.edu/home/collections/ or stop by King Library, on the 3rd floor, room 321.