About a year ago, I wrote about our discovery of two uncatalogued manuscript leaves. Since then, we have hosted a paleography lecture to a class of French literature. Buoyed by positive feedback from the seminar and with intent to hold similar lectures in the future, we made a point this year to broaden our collection of handwriting examples.

Today, I’m happy to announce a wonderful group of additions to our manuscript holdings. Although there is not the mystery surrounding how we came to possess these new leaves, they are nevertheless a wonder to behold.

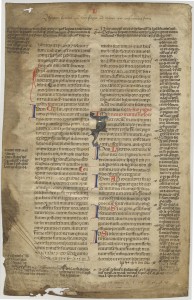

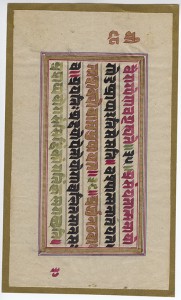

First is a leaf from a circa 1300 AD copy of the Codex Justinianus. The Codex was part of the codification of Roman civil law ordered by Justinian I in the first half of the sixth century AD. This codification, the Corpus Juris Civilis, was the foundation of medieval and modern civil law. Interest in the Corpus saw a huge revival beginning in the 12th century and this leaf is one of a variety of extant examples of a glossed copy of the Codex. The rounded style of gothic writing is commonly called ‘Bolognese’ hand or script, named for the city whose university saw the rebirth of interest in Roman law. This is an example of a medieval ‘glossed’ text, where the original text is bordered on all four sides by commentary.

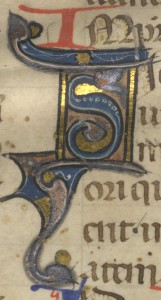

The most obviously striking feature is the illuminated ‘S’ on the verso (back of the leaf). These stylized characters, decorated with gold, represent one of the pinnacles of medieval calligraphy.

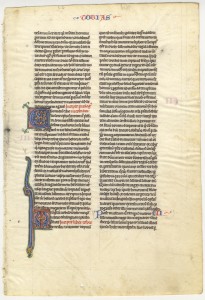

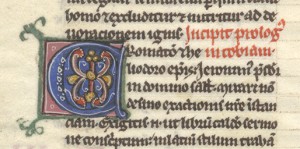

Another new addition to our collection of manuscript leaves is this leaf from a c. 1240 pocket Bible. This leaf is in the same style as the leaf we discovered last year, a remarkably thin piece of vellum with handwriting so minute that an entire Bible could fit into your pocket. In contrast to the other leaf, though, we have a particularly interesting example here for two reasons. Most notable are the illuminated letters on the recto. The recto of the leaf contains the very end of 4 Esdras, the beginning of the Book of Tobit, and, sandwiched between the two books, a copy of Jerome’s prologue to Tobit. In this short prologue (which is actually a letter addressed to the bishops Chromatius and Heliodorus), he describes his translation process. The two bishops had apparently requested this particular book be translated into Latin and Jerome, having only a Chaldean manuscript, found someone who was able to translate the Chaldean to Hebrew which Jerome was then able to translate to Latin. The large illuminated ‘C’ marks the beginning of this prologue.

Because our other pocket Bible leaf is in the middle of a book, we have no way of knowing if the beginning of each book of that manuscript was marked by similar art as this leaf, and so it is exciting to have such an example of illumination to show to students.

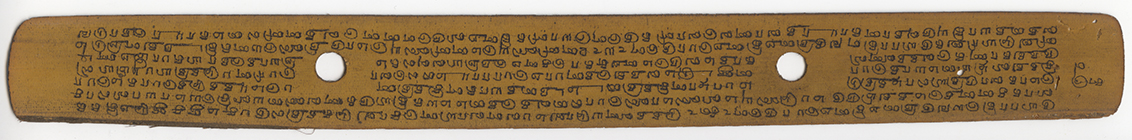

Not all our new acquisitions, though, are examples of Western manucript tradition. Our final addition to our collection of manuscript samples is actually a published collection itself, called Specimens of oriental mss. and printing: a portfolio of original leaves taken from rare oriental books and manuscripts. I love collections like these – another example is our edition of Pages from the past, a collection of manuscript and print examples spanning the history of human writing – and our newest addition is especially exciting for me because I know so little about many of these styles of writing. The publication, fortunately, contains a brief explanation of what each example is. Other languages found in the publication include Syriac, Japanese, Hebrew, and Armenian – what a collection!

As we continue to increase our examples of varied historic hands, I encourage you all to explore these specimens in person. Happy reading,

Marcus Ladd

Special Collection Librarian