Special Collections is home to several portfolio volumes of Pages from the Past: Original Leaves from Rare Books and Manuscripts. Created by The Foliophiles, Inc., Pages from the Past is a collection of “original pages of great 1st Editions, beautiful medieval illuminated manuscripts, ancient papyrus, the works of famous early printers and artists, and precious incunabula ornamented with rare woodcuts.”

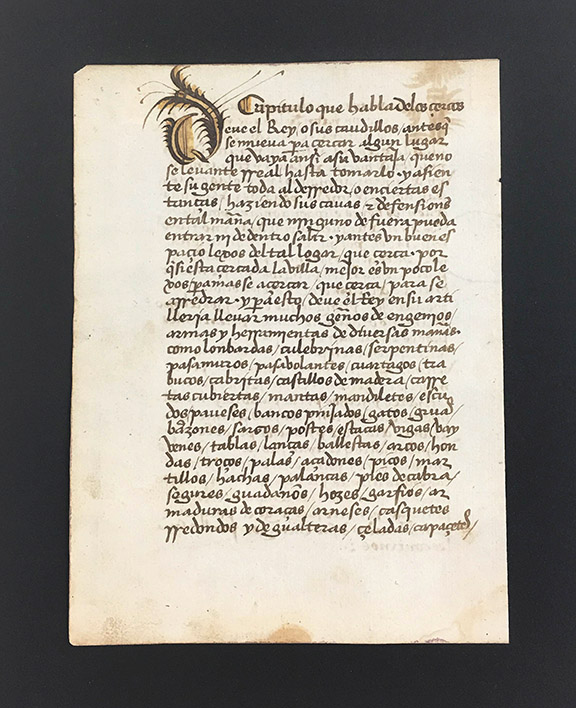

Page from a Portuguese manuscript

The practice of biblioclasty (book-breaking) is a very controversial practice. For many, the idea of breaking apart original books, particularly old ones, is abhorrent. However companies like Foliophiles Inc. approached the practice from an altruistic point of view. The purpose of these broken manuscript sets, as stated by Foliophiles, was to “see placed in libraries and institutions fine leaves of books that might otherwise be entombed in glass cases where none would have the great tactile sense of holding, feeling, reading, and being inspired by a work in the original, as it was created centuries ago.”

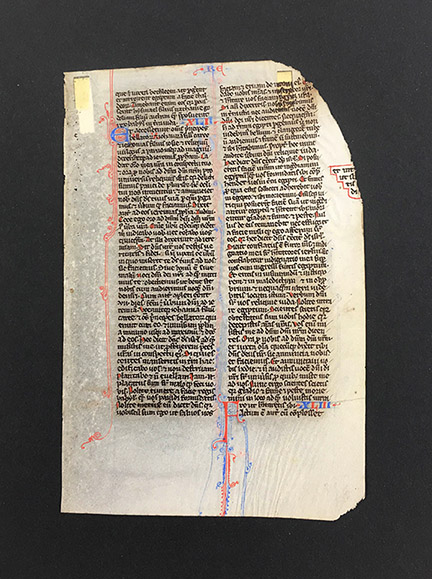

Page from an illuminated manuscript on vellum

While the practice of biblioclasty is itself an interesting topic, I will save that for another time. This post is actually about the variety of preservation issues arising from the Pages from the Past portfolios.

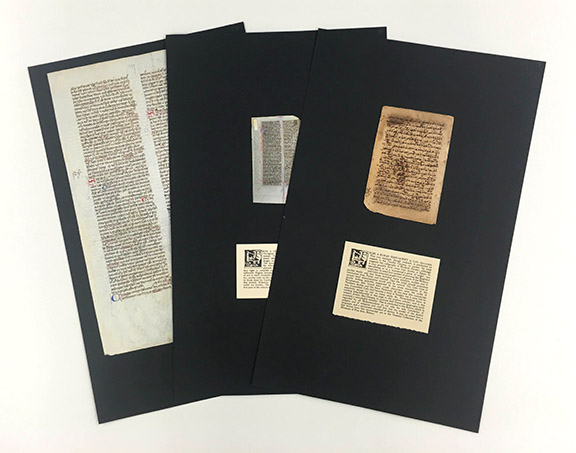

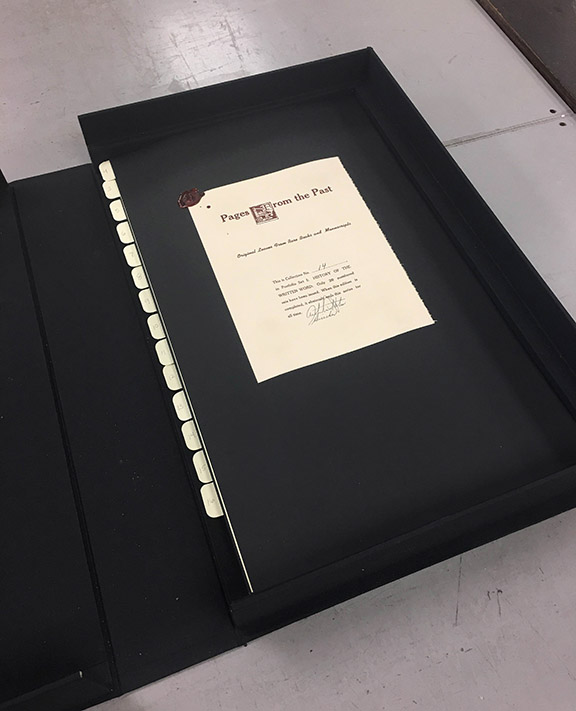

Four volume set of Pages from the Past in their original portfolios

When they were created around 1964, the construction of the portfolios was described by Foliophiles as “encased in a very fine handmade portfolio case. Every leaf is hand-mounted on a uniform sheet of mounting board and attached beneath is a scholarly, printed descriptive label providing complete data and authentication on that particular leaf.” This housing method has created a variety of preservation problems in the years since 1964, both in terms of storage and usability.

Several pages from volume one

At the core of it’s purpose, this collection was meant to be a teaching collection, and that is exactly how it is used here in Special Collections. The large black mounting boards, measuring approximately 13 x 20 inches, make handling the collection difficult and can cause damage to the underlying items. The adhesive used to attach the descriptive text has failed in many cases.

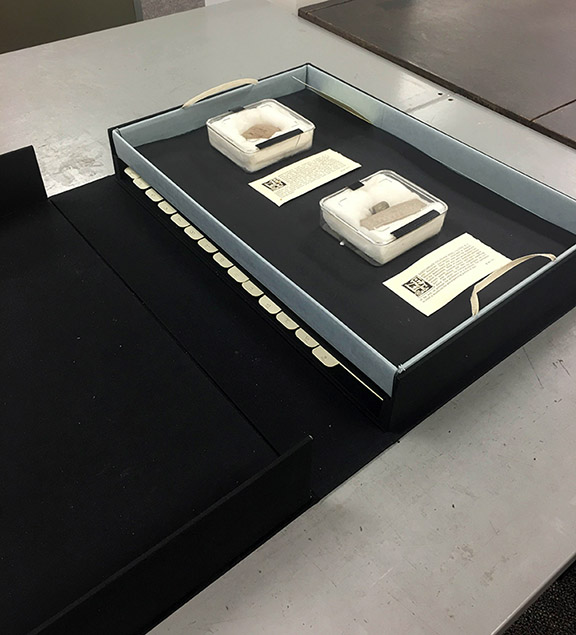

Babylonian clay tablet and cylinder seal

In addition, not every specimen in the portfolios is a flat sheet of paper or vellum. In particular, portfolio one contains several three dimensional items. These items combined with the soft sided portfolio structure has created warping and disfigurement over the years.

Portfolio one warped from three-dimensional objects stored within

The collection was brought to my attention by our Special Collections librarian, and I was asked if there was anything I could do to make handing the collection easier and less damaging. While there were a few different possibilities I could pursue, I had to take into account several things when deciding how to proceed. I did not want to alter the original structure too much. Regardless of how one feels about book breaking, the portfolios do have some artifactual value as objects themselves and as specimens of broken manuscript collections. I also wanted to take a less is more approach. The items could always be revisited later if my solution did not solve the main preservation issues.

Tray created for clay tablets

The first thing I did was create a tray for the three dimensional tablets. This effectively separated them from the flat leaves in the collection in order to eliminate warping.

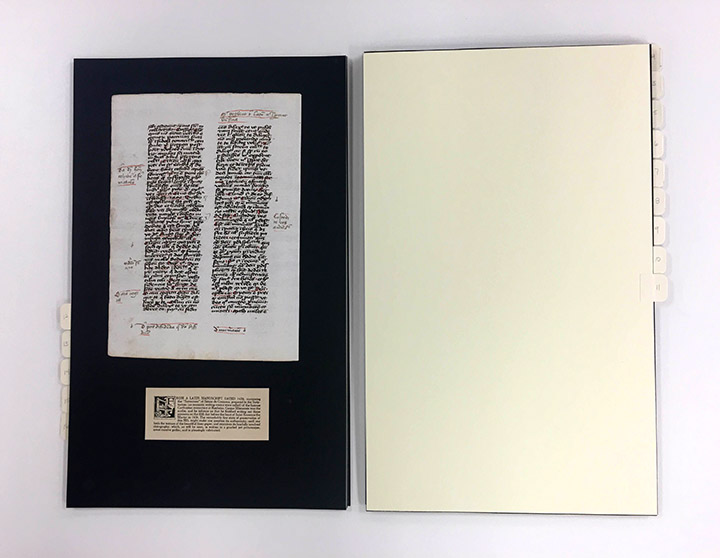

Tabbed dividers between leaves

Next I created tabbed dividers to insert between the remaining flat leaves. These dividers were made of acid-free folder stock and serve two purposes. The numbers on the tabs correspond to the collection inventory list, making it much easier and less damaging to find specific items within the portfolio. The second purpose is to add a protective barrier between the original leaves and the black mat board of the item above.

The leaves sit in the bottom of the clamshell box

The clay tablet tray sits on top of a small ledge in the box

Lastly, I created a new clamshell box to house the entire contents of the portfolio. The flat leaves fit into the bottom of the box, while a small ledge around the sides holds up the top tray, so that it does not rest on the leaves below.

The finished clamshell box

Hopefully, these changes will help preserve the condition of the materials found within, while also preserving the original intent of the collection.

Ashley Jones

Preservation Librarian