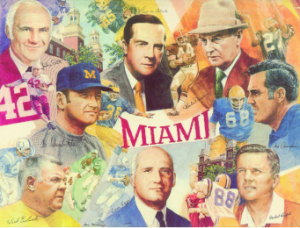

With a heavy heart I write that Miami alumnus Paul Dietzel (Class of ’48) has passed away. The Walter Havighurst Special Collections at Miami University would like to commemorate Dietzel’s life and accomplishments.

Paul Dietzel was born on September 5, 1924 in Fremont, Ohio to Clarence and Catherine Dietzel. Growing up during the Great Depression Dietzel’s family moved around a lot while his father looked for work as a mechanic. They would eventually settle in Mansfield, Ohio. Dietzel played center on the football and basketball teams and threw the discus for the track team. In 1938, Dietzel’s team, Mansfield High School tied Paul Brown’s legendary Massillon team, 6-6, allowing Mansfield to share the Ohio State Championship with Massillon. Paul met his future wife Anne Wilson while in high school at Mansfield. They were married on September 24, 1944.

After graduating from high school, Dietzel received a scholarship to play football and basketball at Duke, despite being recruited heavily by Denison’s assistant coach and future Hall of Famer, Sid Gillman. Gillman eventually became head football coach at Miami University, while Anne was a student and cheerleader. Anne would relay messages from Gillman to Dietzel, encouraging him to transfer to Miami.

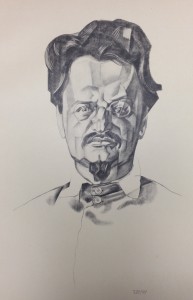

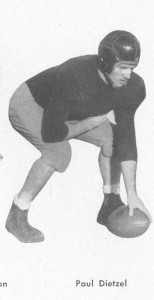

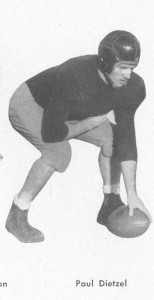

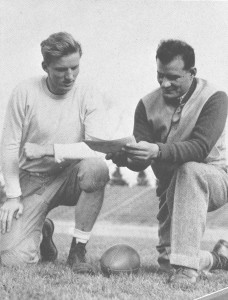

Dietzel as a player at Miami

However, this was during World War II and Dietzel enlisted in the Army Air Corps. While in the Army, Dietzel was stationed all over the country and saw action in the Pacific and Japan. Upon returning to the states he was allowed to leave the Army. He then enrolled at Miami University in 1946.

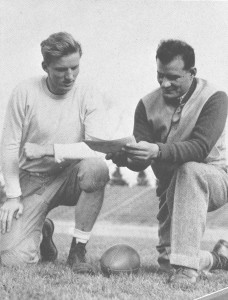

Under Coach Gillman Dietzel played his old position of center on the undefeated 1947 Sun Bowl team. He was also named 2nd team All-American that year. After Dietzel graduated in the fall of ’47, Coach Gillman offered him a graduate assistant position. Dietzel, of course, accepted. However, in a strange turn of events, Gillman was offered the offensive coordinator position at Army by the legendary Earl Blaik after Blaik visited spring practice. He accepted the position and asked Dietzel to come with him. While at Army, Dietzel coached the plebes (freshmen) in football and basketball.

After one season at Army, Gillman accepted the head coaching position at Miami’s rival, Cincinnati. He offered Dietzel the position of defensive coordinator. Dietzel accepted, to Coach Blaik’s chagrin. Dietzel would stay in this position for two years. In 1951 he was offered a position at the University of Kentucky under another future coaching legend, Paul “Bear” Bryant. Moving to the Southeastern Conference (SEC) was a step up, professionally, and after much indecisiveness, he accepted. Dietzel coached the offensive line for “The Bear.”

Dietzel coached at Kentucky for two years before going back to West Point in 1953. Re-joining Blaik’s staff, Dietzel coached the offensive line. After the 1954 season, all four varsity assistant coaches left Army for head coaching positions elsewhere, the last of them being Dietzel. Paul Dietzel was named the head coach of the Louisiana State (LSU) Tigers in 1955, his first head coaching position.

Dietzel’s first three years at LSU were rebuilding years. They hadn’t had a winning season since 1953, or won a bowl game since 1944. In those first three seasons (1955-1957), LSU’s records were 3-5-2, 3-7 and 5-5, respectively. Year four, 1958, was when Dietzel got the program turned around. That year he led the Tigers to a record of 10-0 regular season and a SEC Championship. They were invited to play in the Sugar Bowl against Clemson. LSU was ranked #1 going into the game and Clemson #12. LSU won the game 7-0 and bringing LSU its first National Championship in school history. Dietzel was also named Coach of the Year. He was the youngest coach ever to win the award and also won it by the widest margin ever.

The following year, 1959, LSU was the unanimous selection as preseason #1. They started out that season winning their first seven games including a win over #3 Ole Miss. This brought their winning streak to 19 games, the longest of Dietzel’s career. In the eighth game of the year against Tennessee, LSU lost 14-13. They ended the regular season 9-1 and running back Billy Cannon won the Heisman Trophy, the only person in LSU history to do so. LSU was invited to play in the Sugar Bowl in a rematch against Ole Miss, a team they already defeated. Dietzel did not want to accept, because he felt there was no reason to play a team you had already defeated; fearing the team would not “get up” for a game against a team they had already defeated. Unfortunately, the athletic director felt otherwise and they accepted. Dietzel proved to be right and LSU lost 21-0, ending the season at 9-2.

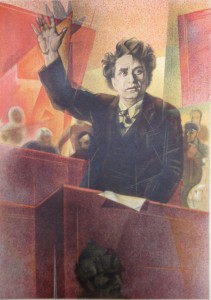

Dietzel with Sid Gillman

Dietzel had a few more successful years at LSU going 5-5 in 1960 and 10-1 in 1961. In seven seasons at LSU Dietzel’s record was 46-24-3 (65%) and 35-7-1 (83%) from 1958 to 1961. They won two SEC Championships (1958 and 1961) and one National Championship (1958). After the 1961 season Dietzel was offered the head coaching position at Army. He accepted and returned to West Point in 1962.

When he was named Army’s head coach, he became the first non-Army graduate to become head coach. Dietzel was the head coach of Army for four seasons, 1962-1965. In those seasons Army had records of 6-4, 7-3, 4-6 and 4-5-1, respectively, for an overall record of 21-18-1 (54%). After the 1965 season Dietzel received a call from the President of the University of South Carolina. Ultimately he was offered the position of head football coach and athletic director with the hopes of turning around South Carolina’s abysmal athletic program.

The athletic department was on probation and in serious debt. Dietzel’s first few years coaching the South Carolina football team were rough. From 1966-1968 South Carolina won 10 games, which was an improvement of the previous three years (9 wins). However, in 1969 Dietzel’s team went 7-4 and finished first in the Athletic Coast Conference (ACC). This was the first time that any team from South Carolina had won a conference championship. They were invited to play in the Peach Bowl. This was only the second time in school history they had played in a bowl game (the other in 1948). Dietzel was named ACC coach of the year that year. Ultimately, his time as head coach of South Carolina was disappointing, record wise; their record 42-53-1 (53%) in Dietzel’s nine years. However, as athletic director he had turned around the program. Season ticket sales for football increased from 3000 to 25000 a year, the department was out of debt and he tremendously upgraded the athletic facilities.

After the 1973 season Dietzel decided to retire as a football coach. He wanted to coach for twenty seasons, and that is what he did. He had wanted to retire from coaching but remain athletic director. Unfortunately, the coach that was hired to replace him was given the athletic director position. He was reassigned to the position of Vice President of University Relations. He was unhappy in his new role and resigned.

Dietzel would not stay unemployed for long. Through an old friend he became aware of a position as commissioner of the Ohio Valley Conference (OVC). He interviewed for and was offered the position. He accepted, but held the position for only one year, 1975.

While commissioner of the OVC he ran into a former colleague, basketball coaching legend Bob Knight. Dietzel and Knight had been head coaches of their respective sports at Army. Knight informed him that the athletic director position at Indiana University (IU) in Bloomington, Indiana, where Knight was currently coaching, was available. Through Knight’s influence (IU had just won the National Championship in basketball) Dietzel was asked to come in for an interview. He was offered the position and accepted. He would remain in Bloomington for two years.

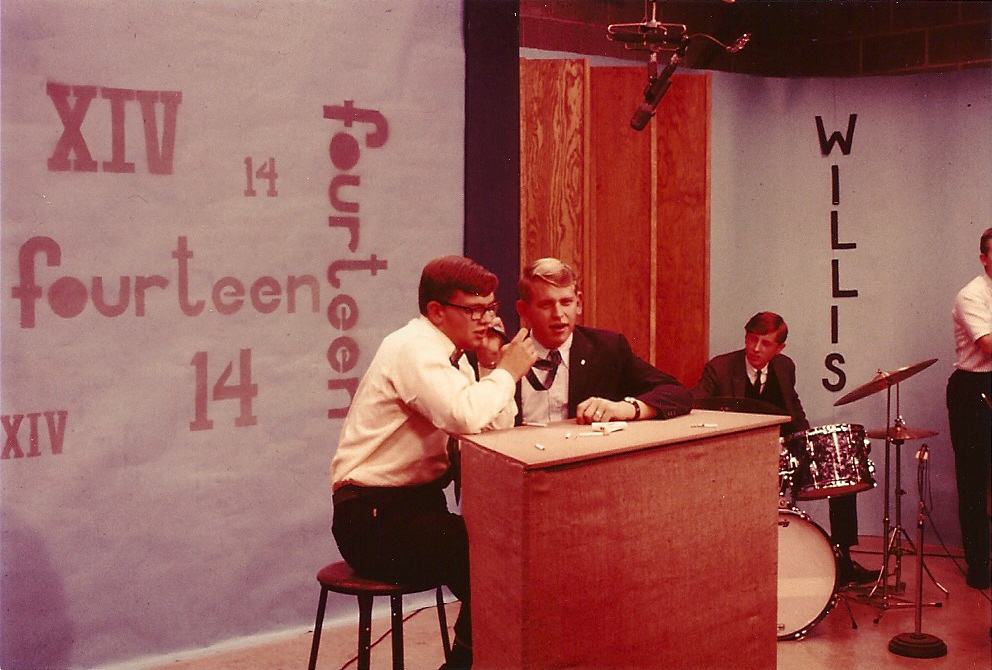

Dietzel with Anne in front of his Statue in the Cradle of Coaches Plaza

In 1978 LSU came calling. Their athletic director had resigned and they asked Dietzel if he was interested. The Dietzels had made a lot of friends in Baton Rouge, but he was a little worried that some people had not forgiven him for leaving in 1961. Ultimately he accepted and returned to LSU in 1978. Dietzel was the athletic director for LSU from 1978 to 1982. Unfortunately, in 1982 he was reassigned to another position within the university. He resigned shortly thereafter.

Upset with the way things happened at LSU, Dietzel and his wife moved to North Carolina. He enjoyed skiing and they had visited their often. During this time he worked in real-estate, as a ski instructor and as a fudge shop owner. The shop was fairly successful and eventually it became too much work for one person and he sold it.

In 1983 he was asked by Samford University to create an athletic department. He accepted the position of Vice President for Athletics. He did not enjoy this work and when his two year agreement was up, in 1985, he retired. After retirement Paul Dietzel and his wife moved back to Baton Rouge. He spent his retirement painting and enjoying time with his wife, kids and grandkids. Dietzel passed away on September 24, 2013 at the age of 89. He is survived by his wife Anne, daughter Kathie DuTremble, son Steve, and two grandchildren.

If you would like to know more about Paul Dietzel, his autobiography, Call Me Coach: A Life in College Football, is available at the Miami University library.

John Cooper

Visiting Librarian

Walter Havighurst Special Collecitons